Brian Bethune reviews The Canadian Century in Maclean’s (third item).

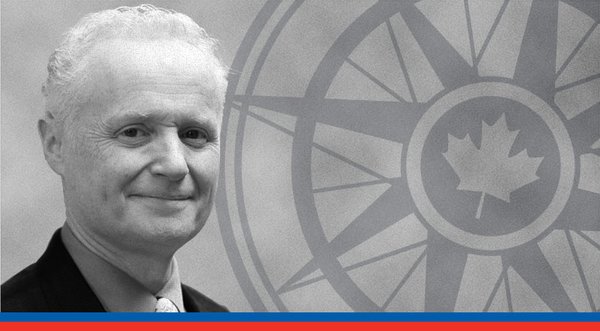

Sir Wilfrid Laurier, as it turns out, was not so much wrong as a shade off in his timing. It’s not the 20th century that would belong to Canada—it’s the 21st, according to Crowley, managing director for the Macdonald-Laurier Institute for Public Policy, and his co-authors in a cheerful (if bracing) survey of our future prospects. Actually, Laurier may not have been even that much wrong: Canadians let the Liberal prime minister down when the benighted electorate rejected free trade in 1911, putting a 78-year crimp in our national potential. But we have grown to love free trade, or at least live with it, and today, write the authors in a book subtitled Moving Out of America’s Shadow, the stars are aligned for Canadian prospects, especially in comparison with our neighbours to the south.

It’s hard to argue with their convincing case. The U.S., as they point out, can’t seem to get its act together in any number of vital areas, from the national debt to tax policy. In contrast, after a hardscrabble decade of reform in the late 1980s and ’90s, Canada has much of its needed institutional infrastructure in place. Our tax structure, despite recent Harper government micromanaging of the sort that sends Crowley et al. around the bend (a tax credit for home reno here, a tax break for transit passes there), is a model of simplicity compared with America’s, which the authors declare to be “nearly impossible for average citizens to navigate” and consequently a burden on the economy. Just about everything else plays out in the same way: the U.S. in the mire for the foreseeable future, Canada looking good. But a clarion call to action, not bragging, is the authors’ aim. Like Canada in the ’90s, America will eventually turn around. If we want to seize our opportunity for a fair share of North American growth, the authors warn, we still have work to do in health care (the costly elephant in the room), and, above all, in ensuring the stimulus deficit doesn’t become permanent.